Ancient Egypt

Joanne O'Brien, ICOREC

The civilization of Ancient Egypt flourished for more than 3,000 years. In the pre-dynastic period Egypt was divided into the kingdoms of Upper and Lower Egypt, the King of Upper Egypt wore the white crown and the King of Lower Egypt wore the red crown. After years of bitter struggle between the kings of the north and the south, the north was finally defeated, Egypt was united under the Southerner, Menes, and the first dynasty was founded around 3100 BCE. The memory of a pre-dynastic Egypt lived on in the pharaohs' title King of Upper and Lower Egypt. The most important periods of Egyptian history are divided into thirty two dynasties which extend from the beginning of the literate period, under the rule of Menes, until Egypt became a Roman province around 30 BCE. The successive pharaohs of Egypt were divided into these dynasties. Throughout her history Egypt passed through periods of turbulent political upheaval and times of peace, power and prosperity. The most stable and productive periods of Egyptian history are marked by the Old, Middle and New Kingdoms. At the end of the New Kingdom Egypt suffered a series of foreign invasions and rulers and the great periods of Egyptian civilization went into decline.

Life in Ancient Egypt revolved around the towns and villages of Egypt which nestled alongside the River Nile. On either side of the river the lands were green and fertile but beyond these narrow strips of land the hot dry desert stretched as far as the horizon. Once the harvest had been collected even the fertile land became hard and dry under the hot desert sun. By late Spring, when the land was desperately parched, the River Nile began to rise. The waters rose gradually, slowly creeping over the land until the fields were hidden from view. When the waters began to recede, leaving behind a thick black layer of silt, villagers and workmen took up their tools and set to work on the land, clearing, digging, surveying, ploughing and planting. The land of Egypt could once more flower with new life, the people would be fed, the taxes paid and the royal granaries well stocked. Each year the land which had been dead was given new life, so at the time of the yearly flood the people celebrated the festival of Osiris, the god of vegetation. The pharaoh, the priests and the people sang, danced and performed plays in his honor, praying for a rich and fruitful harvest. Osiris would give new life to the land, he would also give new life to those who had died, for he was the god of the underworld and he welcomed the dead to his land, the Land of the West.

Until the Middle Kingdom the land of Upper and Lower Egypt was divided into forty two administrative areas known as nomes (maps of the nomes of Lower and Upper Egypt, 6Kb) each governed by a nomarch. The officials of each nome assessed and collected the taxes which were due on the lands which did not belong to the temples and sorted out any minor legal problems in the towns and villages. In theory, the pharaoh owned all the land in Egypt but he gave gifts of land to his favorite subjects. Every large town had at least one temple and the fertile temple lands were exempt from certain taxes and given many privileges. In addition, the king presented foreign booty to the temples and as a result the priesthood became both powerful and wealthy. Sometimes, particularly in the New Kingdom, the power of the priesthood threatened the power of the king himself. The temple was primarily the house of the god cared for by the priesthood and the position of priest was hereditary, though many of the priests had another profession. A doctor could be a priest of Sekhmet, goddess of disease and epidemic, and a lawyer could be a priest of Ma'at, goddess of truth and justice. Once trained these priests would return annually to the temple where they performed religious duties as well as teaching and debating in the universities attached to the temple. These educational institutions were known as the Houses of Life. Doctors, scientists, lawyers, mathematicians and scribes learned their professions alongside each other in the House of Life and religion was interwoven in all these subjects.

The Egyptians put great emphasis on education because it was a means of escaping dirty and often dangerous menial jobs. Before acquiring a profession it was essential to know how to read and write. Ancient Egyptian writing is known as hieroglyphs. Although schoolchildren spent endless hours copying out hieroglyphic literature it was only after training in the House of Life that the scribe could fully master the hieroglyphic script. The Egyptians worked out mathematical formulae for purely practical reasons. They had to know how to divide land and measure area, it was essential to keep exact measurements when the pyramids, tombs or temples were built. While the plans for a building were drawn up by the architects and mathematicians, the workers were busy quarrying the stones. The most common building stones were sandstone, granite and limestone. Since the River Nile was the main highway in Egypt the stones were placed on flat-bottomed barges and floated up the river to the spot nearest the building site. The horse and chariot were not introduced into Egypt until the Middle to New Kingdom but even then the river was the best highway for heavy cargo. With the use of ramps, pulleys and roller sledges the enormous stones were eased up the river banks. The monumental tombs and temples took many years to build so the pharaoh would begin work on his pyramid or tomb during his lifetime. The pyramids were built in layers with the four sides tapering equally. Smooth pathways of earth were laid over stretches of stones so that the stones could be heaved up on sledges with rollers beneath. The Egyptians used the of the human body to determine set lengths; the main measurement was the cubit, equivalent to a man's forearm from the elbow to the tip of the outstretched middle finger.

The desert edge and the eastern hills of Egypt were a rich source of stone which could be cut for use in monumental buildings, for statues or for delicate cosmetic dishes. Stone dishes, particularly alabaster dishes, were made mainly for burial in tombs whereas clay was the material for everyday domestic use. Often the Ancient Egyptians used minerals to paint pots, walls and coffins. For example, soot charcoal could be used for black paint, powdered malachite for green, iron oxide for pink and red ochre for the bright reds. The pigments were ground with a pestle on stone palettes and mixed with water and with glue, gum or egg for adhesive. The abundant clay of the River Nile was combined with water, straw and other vegetable matter to make bricks, the common building material for houses. Clay from the Nile and from the desert wadis was fired to make ceramic storage jars, pots and bowls. Many of the pots were simple, practical and unpainted, designed for use in the home. The Ancient Egyptians were particularly fond of jewelry for decoration in this life and the next. Necklaces, beads, earrings and amulets were made from gold, silver, shell, carnelian, turquoise, amethyst and other precious and semi-precious stones and metals.

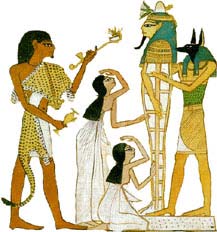

Jewelry was worn by both men and women, particularly on festive occasions but the Egyptians wore very little jewelry and clothing for everyday work in the fields. Most peasants would have worn a small cloth girdle and frequently worked naked. Farming was an important source of labor in Egypt particularly for the people in small villages dotted along the Nile. There was also a demand for craftsmen in the villages or in government workshops. Precious stones were cut and carved to make jewelry for the nobles and the royal family, stonemasons were busy fashioning stones into statues, vases and bowls, carpenters carved fine furniture and statues for houses, temples and tombs. Everybody worked to provide goods for this life as well as the next. The Ancient Egyptians could not imagine the afterlife to be any different from this life. They thought they would still need food, furniture and clothing and to have someone else to plow their lands and prepare their food. So those who could afford it put servant statuettes in their tombs to carry out these tasks. Even the owner of the tomb was usually buried with a statue of himself in case anything should happen to his body. At the burial the officiating priest brought everything to life with sacred words and gestures, this ceremony was known as "the opening of the mouth."

The fertile land of Egypt was scarce and therefore very precious so the dead were buried on the outskirts of towns and villages. In the earliest times they were buried in shallow oval pits dug in the sand with a few goods which they would need in the afterlife: some food, bowls and jewelry. The sun was scorching hot and the sand extremely dry so bodies dried out very quickly. It is possible that sandstorms revealed dead relatives perfectly preserved, this may have been why the people believed that their bodies must be preserved in order to reach the next life. Ancient Egyptian burial became more and more elaborate as time went on. The dead were buried deeper often within a stone chamber and special buildings were put up to mark the grave. These buildings looked like long, low benches and are called "mastabas", an Arabic word for bench. Since the bodies were far away from the drying effects of the sun the skin would rot and eventually all that was left was a skeleton. A way of preserving the body was found through trial and error and the Egyptians learned how to dry out the body so that the skin and hair stayed as it had been in life. This process is known as mummification. During mummification the internal organs were removed by the embalmers through a cut in the lower left hand side of the body. The organs and the body were dried out with a special type of salt known as natron. They were then treated with fragrant spices and perfumes and eventually wrapped in bandages. Special prayers were said over the bandages because each bandage was important, charms were placed next to the skin and between the bandages. These charms are known as "amulets", an Arabic word which means "something which is carried". In life the Ancient Egyptians carried amulets to protect different parts of their bodies and they believed that amulets would ward off evil in the afterlife too.

The pharaoh was far greater than ordinary Egyptians, he was believed to be the son of the great sun god Re. At death the pharaoh joined the sun god in his day boat as he sailed across the sky. At night the sun god changed to his night boat which sailed through the underworld. The pharaohs of the Old Kingdom built huge pyramids of stone which some people thought were like shafts of light coming from the sky, others said it was the place where the pharaoh climbed up to join the sun god. The pharaoh was buried deep inside the pyramid surrounded by all the things he would need for the next life. The pyramids could be seen from great distances and were an easy target for thieves who could break into them at night. The later pharaohs wanted their burials to be safer so they cut their tombs deep into rocks in secret places but even so the thieves found ways of breaking into them.

The sun god Re was one of the most important and oldest gods in Ancient Egypt but there were many others, some were human, some animals while others had animal heads and human bodies. There were favorite gods who would be worshipped on special occasions or in special places. The jackal-headed god Anubis was the god of embalming and guarded the burial place - the necropolis; Seth was the pig god, the evil brother of Osiris, who brought disease and violence; Thoth was the ibis-headed god, the god of writing and wisdom; Horus was the falcon god, son of Osiris and Isis. One god who had an important place in the everyday life of the Ancient Egyptians was the household god, Bes. Bes was depicted as a dwarf deity with ' leonine features and he was affectionately portrayed on bowls, head-rests, mirror handles and other domestic objects. The temple was the house of the god. Each temple was built in the style of the first temple, a simple reed shrine. Tall stone columns carved in the shape of lotus flowers or papyrus buds rose high above the officiating priests. The temples were dark, lit only by windows high up on the walls. The ceilings were painted with stars and the walls were covered in sacred inscriptions and carvings of the gods. The main god of the temple had his sanctuary at the back of the temple and each day the pharaoh or the high priest approached the god's sanctuary to perform the Daily Temple Ritual. The god was washed, fed and dressed and then offered prayers and incense. This important ritual was carried out three times a day in every temple in Egypt.

The monumental temples of Egypt must have appeared daunting to the majority of ordinary people but popular cults did develop around architectural features of the temple. At Memphis, for example, there was a cult of Horus "on the corner of the southern door". Other popular cults grew around the posthumous reputation of famous people, for example, Imhotep, a renowned physician and architect of the third dynasty step pyramid at Saqqara was later worshipped as the god of medicine. Magic also played a central role in Egyptian religion for rich and poor alike. Ritual words, gestures and objects were believed to carry considerable power.

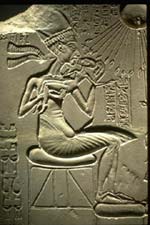

Throughout Egyptian history new gods were accepted into the extensive Egyptian pantheon. At times, however, the literature of the New Kingdom indicates the recognition of a central power behind these countless deities, a power which could be reflected in many forms. This was particularly evident after the reign of the 18th dynasty pharaoh Amenophis IV, who changed his name to Akhenaten and tried to introduce the worship of the Aten as the official Egyptian religion. The Aten's creative power was manifested in the disc of the sun and the pharaoh Akhenaten was his sole representative on earth. After Akhenaten's death there was a move back to traditional cultural practices.

Throughout Egyptian history the diversity of the Egyptian pantheon was welcomed by both the powerful and the humble. The gods permeated most areas of Egyptian life; they could help in sickness and in times of sadness, they could be a cause for celebration or be used as a political tool. Whatever their role they were an essential part of Egyptian life.

Digg This!

![]() Del.icio.us

Del.icio.us

![]() Stumble Upon

Stumble Upon